Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

The Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud is the world’s first distributed cloud-based intelligent component protocol, integrating a wide range of advanced technological solutions such as AI, serverless architecture, full distributed frameworks, relay networks, and various SDKs and APIs. These innovations enable developers to rapidly and seamlessly build decentralized applications (DApps) for Web3, utilizing any programming language while delivering a user experience comparable to Web2 applications.

The Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud is a truly secure Web3 cloud service platform that guarantees user privacy, virtual asset security, and data sovereignty. It offers Web2 application developers comprehensive support—from smart contract development, decentralized storage, and modular components to enhanced information security and privacy protections—significantly reducing the barriers to transitioning from Web2 to Web3 and improving the Web3 user experience.

The Endless was founded with the vision of leveraging technological innovation to empower users with greater autonomy, ensuring data privacy and security. It aims to foster a decentralized co-creation ecosystem where users can create and fully enjoy the value they deserve in the digital world. By shifting the focus of Web3 from financial orientation to practical utility, the Endless seeks to deliver on the promise of decentralized technologies by enabling user empowerment and collaborative value creation.

The core values of Endless include:

Security and Privacy as Foundational Elements

Endless ensures high levels of security and privacy protection for users throughout their interactions by leveraging an advanced data security and privacy architecture. This approach attracts security-conscious user groups, enhances trust in the project, and fosters deeper relationships with potential partners and investors. Endless’s data security and privacy framework relies on several key technologies: dynamic end-to-end encryption, data isolation and access control, zero-knowledge proofs, and storage security based on distributed key management and redundant encryption.

Developer and Project-Centric Modular Design

As a decentralized technology development platform, Endless introduces an innovative distributed cloud component protocol, redefining development approaches through its modular component framework. The Endless distributed cloud component protocol offers an open component marketplace and a rich suite of essential components, enabling developers to easily build and deploy Web3 applications through flexible component combinations without requiring an in-depth understanding of complex blockchain technology. This feature significantly lowers technical barriers, allowing Web2 developers to transition rapidly into the Web3 space.

User-Friendly Design with Low Barriers

To optimize user experience, the Endless introduces a gas subsidy mechanism that allows developers or project teams to cover gas fees required for blockchain transactions. Through this mechanism, users can explore DApp functionalities without bearing transaction costs, particularly beneficial for new users who can experience and understand Web3 applications without financial barriers. This feature also enables developers to promote their DApps more effectively, increasing user engagement and activity. The gas subsidy mechanism holds strategic importance in driving Web3 adoption and promoting application deployment.

AI Integration for Ecosystem Innovation and Enhanced User Experience

Endless deeply integrates AI capabilities with the platform’s decentralized architecture, empowering Web3 applications and accelerating the expansion of value-driven use cases. By incorporating advanced AI models, Endless brings AI capabilities to various application scenarios, such as automated execution of smart contracts, intelligent data analytics, automated processing, personalized recommendations, smart customer service, and dynamic risk management. This integration significantly enhances user experience and application engagement. By embedding AI technology within the Endless platform, developers can streamline their development processes, achieve intelligent user interactions and data processing, and provide users with personalized and efficient services, boosting engagement through precise recommendations and automated workflows.

By integrating AI technology, Endless will leverage decentralized storage solutions to safeguard user data privacy and security, providing users with customized and secure services.

Achieving True Economic Value through Co-Creation

Beyond innovations in technical architecture, Endless supports a truly decentralized co-creation economy. In the Endless ecosystem, users can share in ecosystem growth benefits through their participation and contributions, rather than relying on centralized platforms for value distribution.

Through smart contracts, creator economy innovations, and decentralized governance, the Endless ensures that users receive rewards for contributing content, providing services, or participating in community governance. This approach fosters user engagement, creating a diverse, secure, and user-centric ecosystem. Endless helps users break free from the constraints of traditional centralized platforms, granting them true autonomy and enabling them to earn fair rewards through transparent and equitable mechanisms.

\

Start here to get into the core concepts of the Endless blockchain. Then review our research papers and the Endless source code found in the Endless repository of GitHub while continuing your journey through this site. The source contains READMEs and code comments invaluable to developing on Endless.

If you are new to the Endless blockchain, begin with these tutorials before you get into in-depth development. These tutorials will help you become familiar with how to develop for the Endless blockchain using the Endless SDK.

How to generate, submit and verify a transaction to the Endless blockchain.

Learn the Endless token interface and how to use it to generate your first NFT. This interface is defined in the Move module.

Learn how to deploy and manage a coin. The coin interface is defined in the Move module.

Learn how to deploy and manage a fungible asset. The fungible asset interface is defined in the Move module.

Write your first Move module for the Endless blockchain.

Learn how to perform operations using Off-Chain K-of-N multi-signer authentication.

The Endless blockchain account addresses use Base58 encoding and have the following characteristics:

The length of most regular account addresses is between 43 and 44 characters.

You can quickly differentiate between accounts by checking the first and last few characters of the address.

Vanity addresses are supported.

Sponsored transactions on the Endless chain refer to transactions where the gas fees are paid by the contract invoked by the transaction.

On the Endless blockchain, executing transactions requires a fee, also known as a gas fee, which is typically paid in the native token of the Endless chain (EDS). Gas fees are paid to the validators of the Endless chain to ensure network security. However, for new users, especially those transitioning from Web 2.0, this requirement can increase the barrier to entry.

Sponsored transactions lower the difficulty of interacting with contracts for users, particularly beginners. By leveraging sponsored transaction technology, contracts can make it easier for users to interact while ensuring the contract itself covers the gas fees, thereby maintaining stable chain operations.

Endless is a per-transaction versioned database. When transactions are executed, the resulting state of each transaction is stored separately and thus allows for more granular data access. This is different from other blockchains where only the resulting state of a block (a group of transactions) is stored.

Blocks are still a fundamental unit within Endless. Transactions are batched and executed together in a block. In addition, the proofs within storage are at the block-level granularity. The number of transactions within a block varies depending on network activity and a configurable maximum block size limit. As the blockchain becomes busier, blocks will likely contain more transactions.

Each Endless block contains both user transactions and special system transactions to mark the beginning and end of the transaction batch. Specifically, there are two system transactions:

The EndlessBFT consensus protocol provides fault tolerance of up to one-third of malicious validator nodes.

Mempool is a component within each node that holds an in-memory buffer of transactions that have been submitted to the blockchain, but not yet agreed upon or executed. This buffer is replicated between validator nodes and fullnodes.The JSON-RPC service of a fullnode sends transactions to a validator node's mempool. Mempool performs various checks on the transactions to ensure transaction validity and protect against DOS attacks. When a new transaction passes initial verification and is added to mempool, it is then distributed to the mempools of other validator nodes in the network.When a validator node temporarily becomes a leader in the consensus protocol, consensus pulls the transactions from mempool and proposes a new transaction block. This block is broadcast to other validators and contains a total ordering over all transactions in the block. Each validator then executes the block and submits votes on whether to accept the new block proposal.

Welcome to Move, a next generation language for secure, sandboxed, and formally verified programming. It has been used as the smart contract language for several blockchains including Endless. Move allows developers to write programs that flexibly manage and transfer assets, while providing the security and protections against attacks on those assets. However, Move has been developed with use cases in mind outside a blockchain context as well.

Move takes its cue from by using resource types with move (hence the name) semantics as an explicit representation of digital assets, such as currency.

The purpose of Move programs is to read from and write to tree-shaped persistent global storage. Programs cannot access the filesystem, network, or any other data outside of this tree.

In pseudocode, the global storage looks something like:

Structurally, global storage is a consisting of trees rooted at an account address. Each address can store both resource data values and module code values. As the pseudocode above indicates, each address can store at most one resource value of a given type and at most one module with a given name.

Abstract

The rise of blockchains as a new Internet infrastructure has led to developers deploying tens of thousands of decentralized applications at rapidly growing rates. Unfortunately, blockchain usage is not yet ubiquitous due to frequent outages, high costs, low throughput limits, and numerous security concerns. To enable mass adoption in the web3 era, blockchain infrastructure needs to follow the path of cloud infrastructure as a trusted, scalable, cost-efficient, and continually improving platform for building widely-used applications.

We present the Endless blockchain, designed with scalability, safety, reliability, and upgradeability as key principles, to address these challenges. The Endless blockchain has been developed over the past three years by over 350+ developers across the globe. It offers new and novel innovations in consensus, smart contract design, system security, performance, and decentralization. The combination of these technologies will provide a fundamental building block to bring web3 to the masses:

First, the Endless blockchain natively integrates and internally uses the Move language for fast and secure transaction execution. The Move prover, a formal verifier for smart contracts written in the Move language, provides additional safeguards for contract invariants and behavior. This focus on security allows developers to better protect their software from malicious entities.

Second, the Endless data model enables flexible key management and hybrid custodial options. This, alongside transaction transparency prior to signing and practical light client protocols, provides a safer and more trustworthy user experience.

Third, to achieve high throughput and low latency, the Endless blockchain leverages a pipelined and modular approach for the key stages of transaction processing. Specifically, transaction dissemination, block metadata ordering, parallel transaction execution, batch storage, and ledger certification all operate concurrently. This approach fully leverages all available physical resources, improves hardware efficiency, and enables highly parallel execution.

Fourth, unlike other parallel execution engines that break transaction atomicity by requiring upfront knowledge of the data to be read and written, the Endless blockchain does not put such limitations on developers. It can efficiently support atomicity with arbitrarily complex transactions, enabling higher throughput and lower latency for real-world applications and simplifying development.

Fifth, the Endless modular architecture design supports client flexibility and optimizes for frequent and instant upgrades. Moreover, to rapidly deploy new technology innovations and support new web3 use cases, the Endless blockchain provides embedded on-chain change management protocols.

Finally, the Endless blockchain is experimenting with future initiatives to scale beyond individual validator performance: its modular design and parallel execution engine support internal sharding of a validator and homogeneous state sharding provides the potential for horizontal throughput scalability without adding additional complexity for node operators.

BlockMetadataTransaction - is inserted at the beginning of the block. A BlockMetadata transaction can also mark the end of an epoch and trigger reward distribution to validators.

StateCheckpointTransaction - is appended at the end of the block and is used as a checkpoint milestone.

In Endless, epochs represent a longer period of time in order to safely synchronize major changes such as validator set additions/removals. An epoch is a fixed duration of time, currently defined as two hours on mainnet. The number of blocks in an epoch depends on how many blocks can execute within this period of time. It is only at the start of a new epoch that major changes such as a validator joining the validator set don't immediately take effect among the validators.

Consensus is the component that is responsible for ordering blocks of transactions and agreeing on the results of execution by participating in the consensus protocol with other validator nodes in the network.

Execution is the component that coordinates the execution of a block of transactions and maintains a transient state. Consensus votes on this transient state. Execution maintains an in-memory representation of the execution results until consensus commits the block to the distributed database. Execution uses the virtual machine to execute transactions. Execution acts as the glue layer between the inputs of the system (represented by transactions), storage (providing a persistency layer), and the virtual machine (for execution).

The virtual machine (VM) is used to run the Move program within each transaction and determine execution results. A node's mempool uses the VM to perform verification checks on transactions, while execution uses the VM to execute transactions.

The storage component is used to persist agreed upon blocks of transactions and their execution results to the local database.

Nodes use their state synchronizer component to "catch up" to the latest state of the blockchain and stay up-to-date.

The Move tutorial to cover the basics of programming with Move.

Move Examples demonstrating many different aspects of Move especially those unique to Endless.

Endless Move Framework.

There are several IDE plugins available for Endless and the Move language:

Endless Move Analyzer for Visual Studio.

Move language plugin for JetBrains IDEs: Supports syntax highlighting, code navigation, renames, formatting, type checks and code generation.

The following external resources exist to further your education:

Move was designed and created as a secure, verified, yet flexible programming language. The first use of Move is for the implementation of the Diem blockchain, and it is currently being used on Endless.

This book is suitable for developers who are with some programming experience and who want to begin understanding the core programming language and see examples of its usage.

Begin with understanding modules and scripts and then work through the Move Tutorial.

The target users of Endless include Web2 developers, Web3 developers, project teams, and general users. Addressing the diverse needs and challenges of different user groups, Endless provides comprehensive solutions aimed at promoting the adoption and application of Web3 technology.

Below is a detailed analysis of each target group along with the corresponding application scenarios:

Web3 development involves complex technologies such as smart contracts, decentralized storage, and consensus mechanisms. For developers accustomed to the Web2 technology stack, transitioning to Web3 presents a steep learning curve. Web2 developers typically work with traditional programming languages and frameworks such as JavaScript, Python, and Java. To transition to Web3, they need to master new development languages such as Solidity, Rust, and Move, as well as blockchain technology. This transition not only requires learning an entirely new development paradigm but also demands an in-depth understanding of how decentralized systems operate.

To address the challenges faced by Web2 developers, Endless offers a series of pre-built modules and multi-language SDKs, enabling developers to build DApps using familiar programming languages such as JavaScript and Python. These modular components cover core functionalities such as payments, identity authentication, and data storage, allowing developers to focus on business logic without delving deeply into the underlying technical implementations. Additionally, Endless provides comprehensive documentation, tutorials, and community support to help developers quickly grasp key Web3 development concepts and tools. This not only lowers the learning barrier but also fosters a collaborative ecosystem where developers can share knowledge and insights.

Web3 developers require a high-performance blockchain platform to support the development of complex DApps, particularly those handling high-concurrency user transactions. The efficiency and stability of the system are essential for ensuring a seamless user experience. Furthermore, Web3 developers aim to create innovative functionalities and applications that cater to evolving market demands and user expectations.

For Web3 developers, Endless delivers powerful computing and data processing capabilities to ensure exceptional DApp performance even under high workloads. Its architectural design supports horizontal scalability, allowing for seamless growth in user base and business expansion. Additionally, Endless provides smart contract automation tools and AI-powered analytics, enabling developers to incorporate intelligent elements into contract design and execution. This enhances development efficiency and optimizes the overall intelligence of applications. Using the Endless platform, Web3 developers can build high-frequency trading applications or leverage AI functionalities to automate and refine smart contract execution.

In a highly competitive market environment, increasing user engagement and activity is a key priority for project teams. The ability to attract and retain users effectively is directly linked to the long-term success of a project. Additionally, project teams require efficient tools for managing communities and token economies to ensure sustained community engagement and token market stability.

For project teams, Endless provides an infrastructure that supports multi-currency payments and smart contract security, enhancing transaction convenience and security. Through the platform's token management tools, project teams can effortlessly manage token issuance, distribution, and governance, ensuring a healthy token economy. Additionally, Endless offers a range of private domain operation tools, including precision marketing, airdrop campaigns, and social platform integrations, helping project teams rapidly scale their community presence. These tools not only boost user interaction frequency but also enhance user engagement and loyalty.

Web2 users prioritize data privacy, while Web3 users place greater emphasis on decentralization and transparency. General users expect blockchain applications to provide a user experience comparable to Web2 applications while benefiting from the privacy protection inherent in decentralization. Additionally, users seek to avoid complex operations and high usage costs, aiming for a seamless and intuitive experience akin to traditional internet applications.

To cater to general users, Endless supports developers at both the protocol and component levels in optimizing user interfaces and enabling a seamless transition from Web2 to Web3. This ensures that users can enjoy the convenience and smooth experience of traditional applications. Furthermore, Endless integrates decentralized storage and zero-knowledge proof technologies to safeguard user data privacy and security.

As a blockchain-based ecosystem protocol, Endless has a diversified revenue stream. Below are the monetization models of Endless within the Web3 Genesis Cloud ecosystem:

The Endless Component Marketplace is a decentralized trading platform for components, where developers can publish and sell self-developed components. Users can browse, purchase, and integrate these components into their applications through the Endless platform. All transactions are executed automatically via smart contracts to ensure transparency and security. Endless charges a fixed percentage as a transaction fee for each sale. This fee model not only incentivizes developers to continuously innovate and release high-quality components but also provides a stable revenue stream for the platform.

By offering ready-made and easily integratable components, Endless significantly reduces developers' time to market. These components cover a wide range of functionalities, from user authentication to payment processing, enabling developers to focus on business logic without having to build complex underlying infrastructures. Additionally, Endless continuously expands its component library and offers developer support and marketing promotion services to attract more developers into its ecosystem. This strategy not only enhances the platform's market appeal but also strengthens its competitive edge in the Web3 industry.

Endless offers multi-language SDKs compatible with existing technology stacks, along with comprehensive documentation, tutorials, and technical support to help developers quickly master Web3 development. This lowers the entry barriers for Web2 developers, allowing them to smoothly transition into the Web3 development environment.

The Endless SDK and API follow a pay-per-call billing model, flexible to accommodate the needs of different developers, with fees calculated based on actual usage. Additionally, for enterprise customers requiring long-term and stable services, Endless provides a subscription-based model, enabling users to pay a fixed monthly or annual fee for unlimited or high-quota API access.

Endless offers flexible cloud service packages, allowing developers to choose different storage and bandwidth plans according to the scale and needs of their projects. Its pay-as-you-go model ensures that developers only pay for the resources they actually use, reducing operational costs. Furthermore, leveraging a distributed storage architecture and optimized network acceleration mechanisms, Endless enhances DApp access speed and stability, ensuring a smooth user experience. By providing efficient and secure storage and data transmission services, Endless not only generates a stable revenue stream but also reinforces its market competitiveness.

Endless token holders can stake their tokens to validator nodes to earn network staking rewards. Additionally, as a validator node operator, Endless accepts delegated staking from project teams or individual users and generates revenue through management fees or staking interest. The entire staking process is automated via smart contracts to ensure transparency and security. This mechanism not only creates revenue for the platform but also strengthens the security and stability of the network.

All on-chain transactions within the Endless ecosystem, including component transactions and DApp operations, require Endless tokens for gas fees. A portion of the collected gas fees will be used for token burning to maintain the economic equilibrium, while the remainder will be allocated to validator nodes and the ecosystem fund to support the sustainable development of the Endless ecosystem.

Endless provides a globalized application distribution platform, enabling developers to publish and promote their DApps and mini-programs. The platform is equipped with analytics tools and user feedback systems to help developers optimize their products and enhance user satisfaction. Endless monetizes this service by charging application promotion fees or sharing revenue with developers. This model not only generates economic benefits for the platform but also provides developers with additional exposure and marketing channels. Additionally, Endless regularly hosts developer conferences and application competitions to foster technological innovation and ecosystem collaboration, promoting long-term growth.

Endless builds a vibrant gaming and NFT marketplace to encourage long-term user engagement and increase platform retention. The platform supports user-generated content (UGC), allowing users to create and trade gaming assets or NFT artworks, thus enhancing interaction and fostering a sense of community. Moreover, Endless provides comprehensive tools and resources to empower developers for innovation in Web3 gaming and NFTs. The platform continuously expands its market influence by collaborating with well-known IPs and hosting creative competitions.

In the Web3 gaming sector, Endless generates revenue through in-game economic activities such as virtual item sales and in-game advertisements. In the NFT marketplace, Endless earns revenue by charging a fixed percentage as a transaction fee for NFT sales. Users need to pay transaction fees when conducting NFT trades on the platform. Additionally, Endless offers NFT minting and display services, further diversifying its revenue streams.

The value of the Endless token is a crucial component of the Endless business ecosystem. For more details, please refer to section "5.2 Endless Economic Model."

Account addresses are composed of multiple characters. To ensure the address matches your expectations, checking only the beginning and ending characters is insufficient.

For example, 5SHvmLEaSr76dsKy4XLR5vMht14PRuLzJFx6svJzqorP is an Endless account address.

Currently, addresses in Base58 encoding format are fully supported in both the command line and the block explorer.

Below is an example of how account transactions are displayed on the block explorer:

On the backend, Endless addresses are stored as 32-byte arrays. In some cases, you may see this format in the command line or the browser. For instance, the Endless chain has two system account addresses, represented in hexadecimal format:

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000001, which can be simplified to 0x1. Its role is as the system account, responsible for executing system contracts.

0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000004, which can be simplified to 0x4. Its role is as the system token account, responsible for managing "Tokens" and "NFTs."

To convert between Base58 format and byte format, you can use the following methods:

Online Tools: Search for keywords such as "base58 encoder decoder"

Python Code (requires the base58 library):

import base58

def encode_base58(data: bytes) -> str:

"""Encode bytes into a Base58 string"""

return base58.b58encode(data).decode()

def decode_base58(data: str) -> bytes:

"""Decode a Base58 string into bytes"""

return base58.b58decode(data)struct GlobalStorage {

resources: Map<(address, ResourceType), ResourceValue>

modules: Map<(address, ModuleName), ModuleBytecode>

}Move Scripts are a way to run multiple public functions on Endless in a single transaction. This is similar to deploying a helper module that would do common tasks, but allows for the flexibility of not having to deploy beforehand.

An example would be a function to transfer a half of a user's balance to another account. This is something that is easily programmable, but likely would not need a module deployed for it:

script {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::coin;

use endless_framework::endless_account;

fun transfer_half<Coin>(caller: &signer, receiver_address: address) {

// Retrieve the balance of the caller

let caller_address: address = signer::address_of(caller);

let balance: u64 = coin::balance<Coin>(caller_address);

// Send half to the receiver

let half = balance / 2;

endless_account::transfer_coins<Coin>(caller, receiver_address, half);

}

}Writing scripts

Compiling scripts

Running scripts

For more details on Move Scripts, checkout:

Move Book on Scripts

Tutorial on Scripts

Scenario 1 (under construction)

Scenario 2 (under construction)

Sponsored transactions are implemented at the contract level. Any contract function intending to offer this feature can include the sponsored keyword before the function declaration. This instructs the VM to mark the function as a "sponsored contract function."

Below is an example:

When a transaction invokes the fund function, the gas fees for that transaction will be paid by the contract. Ensure the contract account has sufficient funds to cover these fees; otherwise, the user will encounter an error indicating insufficient tokens to pay the gas fees when submitting the transaction.

Although sponsored functions are easy to implement, consider the following points before using them:

Access Control

External Calls Only

Access Control Determine whether the contract function should be accessible to all users. If the function is intended to sponsor only specific users, implement user checks within the contract to exclude unwanted users. Failing to do so may result in unnecessary gas fee expenses.

External Calls Only Mark the contract function as an entry function to allow only direct user-initiated transactions to call it. Prevent external contracts from invoking the sponsored transaction function to guard against potential attacks.

entry sponsored fun fund(dst_addr: &signer) {

...

}Learn SDKs and try examples on your local node

Learn how to use the component marketplace and the admin panel

Endless CLI

Running a Local Node

Endless Developer Community: Building a Web3 Connector Ecosystem

Endless is a Web3 platform designed to bridge Web2 and AI Agents, providing a foundation for developers to innovate freely. Through an open and collaborative model, Endless lowers the barriers to Web3 development, enabling global developers to share data sovereignty and ecosystem benefits, collectively shaping a decentralized future.

The future of Web3 belongs to every developer willing to explore and innovate. As a project dedicated to the Web3 ecosystem, Endless not only provides a robust technological infrastructure but also offers a comprehensive developer support system to help global developers build high-quality, innovative decentralized applications (DApps) and Web3 infrastructure.

Endless Developer Hub serves as a dedicated platform for developers, focusing on Web3 technology advancements, developer growth, and community co-building, helping developers unlock infinite possibilities.

\

To empower developers in building applications efficiently, Endless Developer Hub provides a comprehensive and well-equipped support system:

Extensive Toolkit: Offers SDKs and API documentation to help developers get started quickly.

Developer Showcase & App Demo: Provides example projects and real-world case studies to lower the development threshold.

Dedicated Technical Support Team: A specialized support team is available to promptly resolve development issues and assist developers in optimizing their projects.

2. Community Support

Building a Strong Developer Network: Developers can communicate and collaborate through multiple channels, including the official developer portal, forums, GitHub open-source community, Medium, and online seminars.

Community Governance Rights: Active contributors gain priority participation in community governance, allowing them to vote on key proposals and shape the future of the ecosystem.

Ecosystem Traffic Support: Developers receive priority access to traffic and market resources within the Endless ecosystem, accelerating their project’s growth.

Ecosystem Partnership Program: By participating in the Endless Ecosystem Partnership Program, developers can collaborate with other projects, share resources, and co-create more application scenarios.

Endless Developer Hub is more than just a technical community; it is an accelerator for developers' growth. If you aspire to make an impact in Web3 and collaborate with top-tier Web3 pioneers worldwide, then this is the place for you!

✅ Comprehensive technical, market, and community support

✅ Direct access to the Endless core team for prompt development assistance

✅ Participation in incentive programs to receive ecosystem support and rewards

✅ Collaborate with top Web3 developers globally to build groundbreaking applications

Whether you are an independent developer or a team looking to explore the future of Web3, we welcome you to join us! 📣 Join the Endless Developer Program! \

Website:

GitHub Community:

EndlessHub Email: [email protected]

Luffa Channel:

Luffa Official Endless Developer Community:

Telegram:If you're looking for new opportunities at the intersection of Web3 & AI, apply for the Endless Ecosystem Incentive Program and build the next generation of innovative applications!

\

address is a built-in type in Move that is used to represent locations (sometimes called accounts) in global storage. An address value is a 256-bit (32-byte) identifier. At a given address, two things can be stored: Modules and Resources.

Although an address is a 256-bit integer under the hood, Move addresses are intentionally opaque---they cannot be created from integers, they do not support arithmetic operations, and they cannot be modified. Even though there might be interesting programs that would use such a feature (e.g., pointer arithmetic in C fills a similar niche), Move does not allow this dynamic behavior because it has been designed from the ground up to support static verification.

You can use runtime address values (values of type address) to access resources at that address. You cannot access modules at runtime via address values.

Addresses come in two flavors, named or numerical. The syntax for a named address follows the same rules for any named identifier in Move. The syntax of a numerical address is not restricted to hex-encoded values, and any valid u256 numerical value can be used as an address value, e.g., 42, 0xCAFE, and 2021 are all valid numerical address literals.

To distinguish when an address is being used in an expression context or not, the syntax when using an address differs depending on the context where it's used:

When an address is used as an expression the address must be prefixed by the @ character, i.e., @<numerical_value> or @<named_address_identifier>.

Outside of expression contexts, the address may be written without the leading @ character, i.e., <numerical_value> or <named_address_identifier>.

In general, you can think of @ as an operator that takes an address from being a namespace item to being an expression item.

Named addresses are a feature that allow identifiers to be used in place of numerical values in any spot where addresses are used, and not just at the value level. Named addresses are declared and bound as top level elements (outside of modules and scripts) in Move Packages, or passed as arguments to the Move compiler.

Named addresses only exist at the source language level and will be fully substituted for their value at the bytecode level. Because of this, modules and module members must be accessed through the module's named address and not through the numerical value assigned to the named address during compilation, e.g., use my_addr::foo is not equivalent to use 0x2::foo even if the Move program is compiled with my_addr set to 0x2. This distinction is discussed in more detail in the section on Modules and Scripts.

The primary purpose of address values are to interact with the global storage operations.

address values are used with the exists, borrow_global, borrow_global_mut, and move_from operations.

The only global storage operation that does not use address is move_to, which uses signer.

As with the other scalar values built-in to the language, address values are implicitly copyable, meaning they can be copied without an explicit instruction such as copy.

Introduction

Modules and Scripts

Move Tutorial

Integers

Bool

Address

Vector

Local Variables and Scopes

Equality

Abort and Assert

Conditionals

Global Storage Structure

Global Storage Operators

Standard Library

Coding Conventions

Node Networks and Synchronization

Validator nodes and fullnodes form a hierarchical structure with validator nodes at the root and fullnodes everywhere else. The Endless blockchain distinguishes two types of fullnodes: validator fullnodes and public fullnodes. Validator fullnodes connect directly to validator nodes and offer scalability alongside DDoS mitigation. Public fullnodes connect to validator fullnodes (or other public fullnodes) to gain low-latency access to the Endless network.

Endless operates with these node types:

Validator nodes (VNs) - participates in consensus and drives transaction processing.

Validator fullnodes (VFNs) - captures and keeps up-to-date on the state of the blockchain; run by the validator operator, so it can connect directly to the validator node and therefore serve requests from public fullnodes. Otherwise, it works like a public fullnode.

Public fullnodes (PFNs) - run by someone who is not a validator operator, PFNs cannot connect directly to a validator node and therefore rely upon VFNs for synchronization.

Archival nodes (ANs) - is a fullnode that contains all blockchain data since the start of the blockchain's history.

The Endless blockchain supports distinct networking stacks for various network topologies. For example, the validator network is independent of the fullnode network. The advantages of having separate network stacks include:

Clean separation between the different networks.

Better support for security preferences (e.g., bidirectional vs server authentication).

Allowance for isolated discovery protocols (i.e., on-chain discovery for validator node's public endpoints vs. manual configuration for private organizations).

Endless nodes synchronize to the latest state of the Endless blockchain through two mechanisms: consensus or state synchronization. Validator nodes will use both consensus and state synchronization to stay up-to-date, while fullnodes use only state synchronization.

For example, a validator node will invoke state synchronization when it comes online for the first time or reboots (e.g., after being offline for a while). Once the validator is up-to-date with the latest state of the blockchain it will begin participating in consensus and rely exclusively on consensus to stay up-to-date. Fullnodes, however, continuously rely on state synchronization to get and stay up-to-date as the blockchain grows.

Each Endless node contains a State Synchronizer component which is used to synchronize the state of the node with its peers. This component has the same functionality for all types of Endless nodes: it utilizes the dedicated peer-to-peer network to continuously request and disseminate blockchain data. Validator nodes distribute blockchain data within the validator node network, while fullnodes rely on other fullnodes (i.e., validator nodes or public fullnodes).

Endless Project Development Goals and Key Milestones

1 Key Areas of Development and Operations

Optimization of Modular Component Protocols:Deepen the stan-dardization of component interface designs and optimize component perfor- mance to enhance flexibility and scalability,allowing adaptation to diverse application scenarios.

\

All Endless releases are available on GitHub: Endless Release

Currently, we offer the endless-cli, endless-node for all platforms, including Ubuntu and Windows. More tools will be released in the future.

Ubuntu 22.04 (x86_64):

Ubuntu-24.04 (x86_64):

Windows (x86_64):

macOS:

Ubuntu 22.04 (x86_64):

Ubuntu-24.04 (x86_64):

Windows (x86_64):

macOS:

Move scripts can be written in tandem with Move contracts, but it's highly suggested to use a separate Move package for it. This will make it easier for you to determine which bytecode file comes from the script.

The package needs a Move.toml and a sources directory, similar to code modules.

For example, we may have a directory layout like:

Scripts can be written exactly the same as modules on Endless. Imports can be used for any dependencies in the Move.toml file, and all public functions, including entry functions, can be called from the contract. There are a few limitations:

There must be only one function in the contract, it will compile to that name.

Input arguments can only be one of [u8, u16, u32, u64, u256, address, bool, signer,

An example below:

For more specific details see: Move Book on Scripts

An Endless node is an entity of the Endless ecosystem that tracks the state of the Endless blockchain. Clients interact with the blockchain via Endless nodes. There are two types of nodes:

Validator nodes

Fullnodes

Each Endless node comprises several logical components:

REST service

Mempool

Execution

Virtual Machine

Storage

State synchronizer

The Endless software can be configured to run as a validator node or as a fullnode.

Fullnodes can be run by anyone. Fullnodes verify blockchain history by either re-executing all transactions in the history of the Endless blockchain or replaying each transaction's output. Fullnodes replicate the entire state of the blockchain by synchronizing with upstream participants, e.g., other fullnodes or validator nodes. To verify blockchain state, fullnodes receive the set of transactions and the accumulator hash root of the ledger signed by the validators. In addition, fullnodes accept transactions submitted by Endless clients and forward them directly (or indirectly) to validator nodes. While fullnodes and validators share the same code, fullnodes do not participate in consensus.

Depending on the fullnode upstream, a fullnode can be called as a validator fullnode, or a public fullnode:

Validator fullnode state sync from a validator node directly.

Public fullnode state sync from other fullnodes.

There's no difference in their functionality, only whether their upstream node is a validator or another fullnode. Read more details about network topology here

Third-party blockchain explorers, wallets, exchanges, and dapps may run a local fullnode to:

Leverage the REST interface for blockchain interactions.

Get a consistent view of the Endless ledger.

Avoid rate limitations on read traffic.

Run custom analytics on historical data.

Move scripts can be compiled with the already existing Endless Move compiler in the Endless CLI. For more on how to install and use the Endless CLI with Move contracts, go to the Working With Move Contracts page.

Once you have the Endless CLI installed, you can compile a script by running the following command from within the script package:

endless move compileThere will then be compiled bytecode files under build/ with the same name as the function in Move.

For example this script in package transfer_half, would compile to build/transfer_half/bytecode_scripts/transfer_half.mv

Additionally, there is a convenience function for a package with exactly one script with the below command:

Providing output like below returning the exact location of the script and a hash for convenience

The vision of the Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud is to achieve true user empowerment and value co-creation through its innovative decentralized technology platform. By enabling Web3 applications that deliver genuine user value, the Genesis Cloud allows users to actively participate in value creation and sharing within the digital economy, thereby propelling Web3 toward sustainable prosperity.

The Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud is a truly secure Web3 cloud service platform that guarantees user privacy, virtual asset security, and data sovereignty. It offers Web2 application developers comprehensive support—from smart contract development, decentralized storage, and modular components to enhanced information security and privacy protections—significantly reducing the barriers to transitioning from Web2 to Web3 and improving the Web3 user experience.

The Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud is the world’s first distributed cloud-based intelligent component protocol, integrating a wide range of advanced technological solutions such as AI, serverless architecture, full distributed frameworks, relay networks, and various SDKs and APIs. These innovations enable developers to rapidly and seamlessly build decentralized applications (DApps) for Web3, utilizing any programming language while delivering a user experience comparable to Web2 applications.

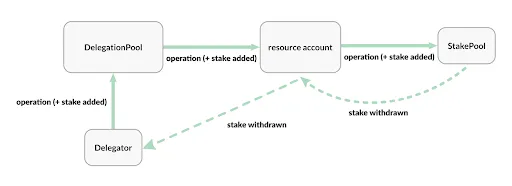

A is a developer feature used to manage resources independent of an account managed by a user, specifically publishing modules and providing on-chain-only access control, e.g., signers.

Typically, a resource account is used for two main purposes:

Store and isolate resources; a module creates a resource account just to host specific resources.

When first creating an object, it will have a resource named 0x1::object::ObjectCore added. This contains metadata about the object, as well as information about the owner of the object.

Objects can be created in multiple ways depending on your needs. They can be broken into two main types of objects:

Deletable objects

On Endless, on-chain state is organized into resources and modules. These are then stored within the individual accounts. This is different from other blockchains, such as Ethereum, where each smart contract maintains their own storage space. See Accounts for more details on accounts.

Move modules define struct definitions. Struct definitions may include the abilities such as key or store. Resources are struct instance with The key ability that are stored in global storage or directly in an account. The store

The Move language controls access to resources using the store ability and accounts. The Object model provides a way to associate a collection of resources with a single address, using centralized resource control and ownership management. An Object is a container for resources at a single address which can be managed and accessed as a group for efficiency. The contract creating an Object can define custom behaviors around changes and transfers of those resources.

It's simply represented as an ObjectCore struct, which keeps track of the owner of the Object and transfer permissions. Along with the ability to store resources with an ObjectGroup. You can find more technical details at the Object standard page, and view the code at the framework generated object documentation.

Endless allows for permissionless publishing of modules within a package as well as upgrading those that have appropriate compatibility policy set.

A module contains several structs and functions, much like Rust.

During package publishing time, a few constraints are maintained:

Both Structs and public function signatures are published as immutable.

Only when a module is being published for the first time, and not during an upgrade, will the VM search for and execute an init_module(account: &signer) function. The signer of the account that is publishing the module is passed into the init_module

References

Tuples and Unit

Functions

Structs and Resources

Constants

Generics

Type Abilities

Uses and Aliases

Friends

Packages

Package Upgrades

Unit Tests

Get notifications about particular on-chain events.

It represents an important transformation from traditional blockchain technologies to Web3 application technologies. Nowadays, many blockchain solutions focus on specific fields, such as decentralized finance (DeFi) and social media. However, the rise of Web3 has brought the need for broader application support. The applications and solutions of Endless in these fields demonstrate its innovative ability and market adaptability in the Web3 ecosystem, providing strong support and broad application prospects for users, developers, and project parties/enterprises.

The Web3 ecosystem holds great potential, but its mass adoption also faces some challenges and certain development barriers.

High Development Barriers

The Web3 development environment presents significant technical challenges for traditional Web2 developers, requiring in-depth knowledge of blockchain infrastructure. These technologies differ substantially from the centralized architectures and technical logic of Web2 development.

Data Privacy and Security

Web3 technology enhances data privacy and security theoretically, but there are still many shortcomings in its practical application. Vulnerabilities in smart contracts and inadequate private key management can lead to data breaches and asset loss. Current Web3 platforms have notable deficiencies in privacy protection and security, causing investor skepticism regarding data privacy capabilities.

Immature Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Web3

AI has significant potential in Web3, offering innovations in smart contract optimization, data analysis, and automated decision-making. However, the integration of AI and Web3 is still in its infancy, with many potential applications underdeveloped and underutilized.

Technical Fragmentation and Poor Interoperability

The Web3 ecosystem suffers from fragmented technical standards, creating significant interoperability challenges that hinder collaboration and growth. Different chains employ distinct protocols and technology stacks, making cross-chain operations complex and costly, limiting seamless interactions for users and developers across chains.

Poor User Experience and Limited Ecosystem

The user experience of Web3 applications is often less smooth than that of Web2 applications. Additionally, the current Web3 application ecosystem remains relatively narrow, with limited diversity in application scenarios, restricting user choice and experience.

In response to the market pain points mentioned above, the Endless provides its solutions through various technological and mechanism innovations. It provides a secure, privacy-first, and decentralized environment that establishes a robust foundation for a diverse Web3 ecosystem, enabling users to co-create and share in the economic system.

The core of Web3 Genesis Cloud lies in co-creation. By leveraging efficient decentralized components, it has established a highly flexible and user-friendly development platform. The platform integrates a variety of technological solutions, including AI, serverless architecture, fully distributed frameworks, relay networks, and a wide range of SDKs and APIs, significantly lowering the technical barriers for developers entering the Web3 space. Through decentralized networks, distributed storage, smart contracts, zero-knowledge (ZK) technology, and cross-chain solutions, it ensures data asset security and privacy protection. Moreover, its innovative architecture supports a wide array of application scenarios.

These technical and innovative solutions collectively establish Endless’s competitive edge and innovation in the Web3 space. Within the Genesis Cloud’s co-creative Web3 economic ecosystem, users (community members) are no longer passive consumers or subjects of financial speculation but active contributors and beneficiaries. They can create value through content creation, service provision, and community governance, earning rewards within the ecosystem via a token economy model. Unlike traditional Web2, the Genesis Cloud transforms users from “products” into true partners within the ecosystem. Moreover, compared to existing Web3 infrastructures, the Genesis Cloud is directed towards supporting applications with real-world value, genuinely delivering economic value to users.

As a distributed cloud-based intelligent component Protocol, Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud aims to serve Web2 developers in seamlessly transitioning to Web3, laying the foundation for the prosperity of large-scale Web3 applications and creating value for Web3 users.

To achieve this, Endless Web3 Genesis Cloud builds a rich and convenient Web3 infrastructure foundation, encapsulating key components and capabilities including Super Stack, AI components, decentralized network services, and the Endless public chain, thereby creating an efficient, composable, privacy-protecting, and easy-to-use development ecosystem. In this ecosystem, large-scale, high-concurrency Web3 super applications—such as social media, short videos, music, cross-border e-commerce, as well as AI and financial applications—can thrive and expand freely. This is also Endless's ecological vision.

We invite developers, entrepreneurs, and technological innovators from around the world to explore the opportunities provided by Endless. By using our protocol, you can turn your ideas into reality faster and build innovative Web3 applications. Endless provides the necessary tools and support to help you find and seize new business opportunities in this rapidly evolving field. Let's work together to leverage the advantages of the Endless protocol and promote the growth and prosperity of the Web3 ecosystem. Your participation and innovation are key to driving this field forward.

\

Literals for bool are either true or false.

bool supports three logical operations:

&&

short-circuiting logical and

p && q is equivalent to if (p) q else false

||

short-circuiting logical or

p || q is equivalent to if (p) true else q

!

logical negation

!p is equivalent to if (p) false else true

bool values are used in several of Move's control-flow constructs:

if (bool) { ... }

while (bool) { .. }

assert!(bool, u64)

As with the other scalar values built-in to the language, boolean values are implicitly copyable, meaning they can be copied without an explicit instruction such as copy.

Publish module as a standalone (resource) account, a building block in a decentralized design where no private keys can control the resource account. The ownership (SignerCap) can be kept in another module, such as governance.

In Endless, a resource account is created based upon the SHA3-256 hash of the source's address and additional seed data. A resource account can be created only once; for a given source address and seed, there can be only one resource account. That is because the calculation of the resource account address is fully determined by the former.

An entity may call create_account in an attempt to claim an account ahead of the creation of a resource account. But if a resource account is found, Endless will transition ownership of the account over to the resource account. This is done by validating that the account has yet to execute any transactions and that the Account::signer_capbility_offer::for is none. The probability of a collision where someone has legitimately produced a private key that maps to a resource account address is improbably low.

The easiest way to set up a resource account is by:

Using Endless CLI: endless account create-resource-account creates a resource account, and endless move create-resource-account-and-publish-package creates a resource account and publishes the specified package under the resource account's address.

Writing custom smart contracts code: in the resource_account.move module, developers can find the resource account creation functions create_resource_account, create_resource_account_and_fund, and create_resource_account_and_publish_package. Developers can then call those functions to create resource accounts in their smart contracts.

Each of those options offers slightly different functionality:

create_resource_account - merely creates the resource account but doesn't fund it, retaining access to the resource account's signer until explicitly calling retrieve_resource_account_cap.

create_resource_account_and_fund - creates the resource account and funds it, retaining access to the resource account's signer until explicitly calling retrieve_resource_account_cap.

create_resource_account_and_publish_package - creates the resource account and results in loss of access to the resource account by design, because resource accounts are used to make contracts autonomous and immutable.

In this example, you will initialize the mint_nft module and retrieve the signer capability from both the resource account and module account. To do so, call create_resource_account_and_publish_package to publish the module under the resource account's address.

Initialize the module as shown in the minting.move example.

Call create_resource_account_and_publish_package to publish the module under the resource account's address, such as in the mint_nft.rs end-to-end example.

Retrieve the signer cap from the resource account + module account as shown in the minting.move example.

Note, if the above resource_account signer is not already set up as a resource account, retrieving the signer cap will fail. The source_addr field in the retrieve_resource_account_cap function refers to the address of the source account, or the account that creates the resource account.

For an example, see the SignerCapability employed by the mint_nft function in minting.move.

For more details, see the "resource account" references in resource_account.move and account.move.

The new Endless Digital Asset Standard allows:

Rich, flexible assets and collectibles.

Easy enhancement of base functionality to provide richer custom functionalities. An example of this is the endless_token module

Digital Asset (DA) is recommended for any new collections or protocols that want to build NFT or semi-fungible tokens.

The new Endless Fungible Asset Standard is a standard meant for simple, type-safe, and fungible assets based on object model intending to replace Endless coin. Fungible Asset (FA) offers more features and flexibility to Endless move developers on creating and managing fungible assets.

The Wallet standard ensures that all wallets use the same functionality for key features. This includes:

The same mnemonic so that wallets can be moved between providers.

Wallet adapter so that all applications can interact seamlessly with a common interface.

&signervector<u8>my_project/

├── Move.toml

└── sources/

└── my_script.move

script {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::coin;

use endless_framework::endless_account;

fun transfer_half<Coin>(caller: &signer, receiver_address: address) {

// Retrieve the balance of the caller

let caller_address: address = signer::address_of(caller);

let balance: u64 = coin::balance<Coin>(caller_address);

// Send half to the receiver

let half = balance / 2;

endless_account::transfer_coins<Coin>(caller, receiver_address, half);

}

}endless move compile-scriptNon-deletable objects

Generally, users want objects to be deletable. If an object is deletable, then storage refunds can be acquired by deleting the object, saving on gas.

Create object generates a random unique address based on the transaction hash and a counter. The addresses of the objects are always unique and this is the preferred way to make most objects.

Non-deletable objects are useful for certain situations that need a guarantee of an existing object. There are two ways to handle this on Endless:

Named objects

Sticky objects

Create named object lets you create an object with a fixed seed. This makes it easy to later

This is exactly the same as deletable objects, but the object cannot be deleted. This is necessary for uses like fungible asset metadata that would want to not be deleted.

The Coin instance can be taken out of CoinStore with the owning account's permission and easily transferred to another CoinStore resource. It can also be kept in any other custom resource, if the definition allows, for example:

All instances and resources are defined within a module that is stored at an address. For example 0x1234::coin::Coin<0x1234::coin::SomeCoin> would be represented as:

In this example, 0x1234 is the address, coin is the module, Coin is a struct that can be stored as a resource, and SomeCoin is a struct that is unlikely to ever be represented as an instance. The use of the phantom type allows for there to exist many distinct types of CoinStore resources with different CoinType parameters.

Permissions of resources and other instances are dictated by the module where the struct is defined. For example, an instance within a resource may be accessed and even removed from the resource, but the internal state cannot be changed without permission from the module where the instance's struct is defined.

Ownership, on the other hand, is signified by either storing a resource under an account or by logic within the module that defines the struct.

Resources are stored within accounts. Resources can be located by searching within the owner's account for the resource at its full query path inclusive of the account where it is stored as well as its address and module. Resources can be viewed on the Endless Explorer by searching for the owning account or be directly fetched from a fullnode's API.

The module that defines a struct specifies how instances may be stored. For example, events for depositing a token can be stored in the receiver account where the deposit happens or in the account where the token module is deployed. In general, storing data in individual user accounts enables a higher level of execution efficiency as there would be no state read/write conflicts among transactions from different accounts, allowing for seamless parallel execution.

The conditional expressions may produce values so that the if expression has a result.

The expressions in the true and false branches must have compatible types. For example:

If the else clause is not specified, the false branch defaults to the unit value. The following are equivalent:

Commonly, if expressions are used in conjunction with expression blocks.

if-expression → if ( expression ) expression else-clauseopt

else-clause → else expression

if (x > 5) x = x - 5if (y <= 10) y = y + 1 else y = 10An example of creating and transferring an object:

Creating objects

Configuring objects

Using objects

For more details on objects, checkout:

Object standards page.

Framework generated object documentation

let a1: address = @0x1; // shorthand for 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

let a2: address = @0x42; // shorthand for 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000042

let a3: address = @0xDEADBEEF; // shorthand for 0x00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000DEADBEEF

let a4: address = @0x000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000A;

let a5: address = @std; // Assigns `a5` the value of the named address `std`

let a6: address = @66;

let a7: address = @0x42;

module 66::some_module { // Not in expression context, so no @ needed

use 0x1::other_module; // Not in expression context so no @ needed

use std::vector; // Can use a named address as a namespace item when using other modules

...

}

module std::other_module { // Can use a named address as a namespace item to declare a module

...

}script {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::coin;

use endless_framework::endless_account;

fun transfer_half<Coin>(caller: &signer, receiver_address: address) {

// Retrieve the balance of the caller

let caller_address: address = signer::address_of(caller);

let balance: u64 = coin::balance<Coin>(caller_address);

// Send half to the receiver

let half = balance / 2;

endless_account::transfer_coins<Coin>(caller, receiver_address, half);

}

}Compiling, may take a little while to download git dependencies...

UPDATING GIT DEPENDENCY https://github.com/endless-labs/endless.git

INCLUDING DEPENDENCY EndlessFramework

INCLUDING DEPENDENCY EndlessStdlib

INCLUDING DEPENDENCY MoveStdlib

BUILDING transfer_half

{

"Result": {

"script_location": "/opt/git/developer-docs/apps/docusaurus/static/move-examples/scripts/transfer_half/script.mv",

"script_hash": "9b57ffa952da2a35438e2cf7e941ef2120bb6c2e4674d4fcefb51d5e8431a148"

}

}module my_addr::object_playground {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::object;

entry fun create_my_object(caller: &signer) {

let caller_address = signer::address_of(caller);

let constructor_ref = object::create_object(caller_address);

// ...

}

}module my_addr::object_playground {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::object;

/// Seed for my named object, must be globally unique to the creating account

const NAME: vector<u8> = b"MyAwesomeObject";

entry fun create_my_object(caller: &signer) {

let caller_address = signer::address_of(caller);

let constructor_ref = object::create_named_object(caller_address, NAME);

// ...

}

#[view]

fun has_object(creator: address): bool {

let object_address = object::create_object_address(&creator, NAME);

object_exists<0x1::object::ObjectCore>(object_address)

}

}module my_addr::object_playground {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::object;

entry fun create_my_object(caller: &signer) {

let caller_address = signer::address_of(caller);

let constructor_ref = object::create_sticky_object(caller_address);

// ...

}

}/// A holder of a specific coin type and associated event handles.

/// These are kept in a single resource to ensure locality of data.

struct CoinStore<phantom CoinType> has key {

coin: Coin<CoinType>,

}

/// Main structure representing a coin/token in an account's custody.

struct Coin<phantom CoinType> has store {

/// Amount of coin this address has.

value: u64,

}struct CustomCoinBox<phantom CoinType> has key {

coin: Coin<CoinType>,

}module 0x1234::coin {

struct CoinStore<phantom CoinType> has key {

coin: Coin<CoinType>,

}

struct SomeCoin { }

}let z = if (x < 100) x else 100;// x and y must be u64 integers

let maximum: u64 = if (x > y) x else y;

// ERROR! branches different types

let z = if (maximum < 10) 10u8 else 100u64;

// ERROR! branches different types, as default false-branch is () not u64

if (maximum >= 10) maximum;if (condition) true_branch // implied default: else ()

if (condition) true_branch else ()let maximum = if (x > y) x else y;

if (maximum < 10) {

x = x + 10;

y = y + 10;

} else if (x >= 10 && y >= 10) {

x = x - 10;

y = y - 10;

}module my_addr::object_playground {

use std::signer;

use endless_framework::object::{self, ObjectCore};

entry fun create_and_transfer(caller: &signer, destination: address) {

// Create object

let caller_address = signer::address_of(caller);

let constructor_ref = object::create_object(caller_address);

// Set up the object...

// Transfer to destination

let object = object::object_from_constructor_ref<ObjectCore>(

&constructor_ref

);

object::transfer(caller, object, destination);

}

}Genesis and Waypoint

Chain ID

220

221

Epoch duration

7200 seconds

7200 seconds

Network providers

Fully decentralized.

Managed by Endless on behalf of Endless Foundation.

Release cadence

Monthly

Monthly

Wipe cadence

Never.

Never.

Purpose

The main Endless network.

Long-lived test network.

Network status

Always live.

Always live.

REST API

REST API Spec

Account

Transaction

Resources

Events

Native Token

SDKs

Faucet

First Transaction

Your First Move Module

Move Book

Endless RPC

User Guide

Developer User Guide

Due to the comparatively massive volumes sold during early-stage rounds, projects may encounter extreme selling pressure after the IDO and after the token has been posted on Centralized Exchange – CEX / Decentralized Exchange – DEX. It significantly lowers the price of tokens by increasing the total amount of tokens in circulation.

For the Token Economy to stay sustainable & effective, the majority of tokens must be kept by investors rather than being sold on the market. Members can stop the value of its token from sinking by locking up tokens. Additionally, it prevents team members from selling their tokens as soon as trade begins, safeguarding holders’ interests.

Endless's locking_coin_ex contract manages token distribution via a locking and unlocking mechanism, ensuring gradual token release over a defined period to control circulation.

The contract allows any user to:

Lock any amount of any fungible token, including native EDS.

Specify the recipient account for unlocked tokens.

Define a two-stage release plan:

Specify a portion of tokens for immediate release at a designated epoch.

The following are the main API interfaces provided by this contract:

total_locks(token_address: address): u128

Function: Query the total locked amount for the specified token address.

Parameters: token_address - The token address.

Return value: Total locked amount.

public fun get_all_stakers(token_address: address): vector<address>

Function: Query all staker addresses for the specified token address.

Parameters: token_address - The token address.

Return value: List of staker addresses.

public fun staking_amount(token_address: address, recipient: address): u128

Function: Query the staking amount for the specified staker at the specified token address.

Parameters: token_address - The token address, recipient - The staker address.

Return value: Staking amount.

the structure contains receiver's address when release, and next release plan(amount and related epoch)

public fun get_all_stakers_unlock_info(token_address: address): vector<UnlockInfo>

Function: Query the unlock information for all stakers at the specified token address.

Parameters: token_address - The token address.

Return value: List of unlock information.

public fun get_unlock_info(token_address: address, sender: address): UnlockInfo

Function: Query the unlock information for the specified staker at the specified token address.

Parameters: token_address - The token address, sender - The staker address.

Return value: Unlock information.

public entry fun add_locking_plan_from_unlocked_balance(sender: &signer, token_address: address, receiver: address, total_coins: u128, first_unlock_bps: u64, first_unlock_epoch: u64, stable_unlock_interval: u64, stable_unlock_periods: u64)

Function: Add a locking plan from the unlocked balance.

Parameters:

sender - The signer,

token_address - The token address,

public entry fun add_locking_plan(sender: &signer, token_address: address, receiver: address, total_coins: u128, first_unlock_bps: u64, first_unlock_epoch: u64, stable_unlock_interval: u64, stable_unlock_periods: u64)

Function: Add a locking plan.

Parameters:

sender - The signer,

token_address - The token address,

public entry fun claim(sender: &signer, token_address: address, amount: u128)

Function: Claim unlocked tokens.

Parameters:

sender - The signer,

token_address - The token address,

An account on the Endless blockchain represents access control over a set of assets including on-chain currency and NFTs. In Endless, these assets are represented by a Move language primitive known as a resource that emphasizes both access control and scarcity.

Each account on the Endless blockchain is identified by a (base58 encoded) account address.

Different from other blockchains where accounts and addresses are implicit, accounts on Endless are explicit and need to be created before they can execute transactions. The account can be created explicitly or implicitly by transferring Endless tokens (EDS) there. See the Creating an account section for more details. In a way, this is similar to other chains where an address needs to be sent funds for gas before it can send transactions.

There are three types of accounts on Endless:

Standard account - This is a typical account corresponding to an address with a corresponding pair of public/private keys.

Resource account - An autonomous account without a corresponding private key used by developers to store resources or publish modules on-chain.

Object - A complex set of resources stored within a single address representing a single entity.

Account address example

Account addresses are Base58-encoded strings derived from 32-byte values, typically have a length of approximately 43 characters. See the Your First Transaction for an example of how an address appears, reproduced below:

Alice: BtXV19CoB1F3maLzzmmV8UaSZC4Jo3wHU9PDHeuwDo99

When a user requests to create an account, for example by using the Endless, the following steps are executed:

Select the authentication scheme for managing the user's account, e.g., Ed25519.

Generate a new private key, public key pair.

Combine the public key with the public key's authentication scheme to generate a 32-byte authentication key and the account address.

The user should use the private key for signing the transactions associated with this account.

The sequence number for an account indicates the number of transactions that have been submitted and committed on-chain from that account. Committed transactions either execute with the resulting state changes committed to the blockchain or abort wherein state changes are discarded and only the transaction is stored.